In Control of the Self

/Hanging at the front of the Jundokan So-Honbu Dojo, just above the four golden principles and the Busaganashi, are two large calligraphy prints.

These prints read 究道無限 (kyūdōmugen) and 心身自在 (shinshinjizai).

On the left side of the dojo, we have 究道無限 (kyūdōmugen), the four characters of which can be broken down as follows:

From this, it is easy to understand that 究道無限 (kyūdōmugen) literally means “the road of research is never ending”, simply emphasising the continuous, ongoing state of our studying and understanding the art of Gojū-Ryū, no matter what level we reach.

On the other hand, we have 心身自在 (shinshinjizai), which is by far the deeper of the two phrases, and is thus what I want to focus on today.

First, let’s break down the four kanji characters used:

From this meaning alone, one can guess that 心身自在 (shinshinjizai) means “the heart and body exist within the self”. But what exactly does that entail?

In short, the overall meaning is something like “you are in control of your own body and mind”. But after a very productive talk with Miyakozawa-sensei of the Jundokan, I discovered that there are actually three distinct interpretations of this meaning.

1.) Don’t be influenced by others.

This interpretation is related to the Japanese word 動じる (dōjiru), which means “to be agitated” or “to be upset” by something or someone. In short, this idea refers to not being influenced emotionally by the actions or words of others around you, particularly in a way that might encourage you to act out physically in response (and thus use your karate in the wrong way).

2.) Keep control of your mind (emotions) and body (actions).

This interpretation is grounded in the idea of 不動心 (fudōshin), meaning “steadfastness”. It refers to “keeping calm” (e.g., during a fight) or “keeping a cool head” (e.g., in an emergency). In other words, it emphasises the importance of being able to control your emotions (and your body by extension) in times when you may be forced to use karate to defend yourself.

This is further related to an understanding of the term 自由自在 (jiyūjizai), meaning “flexibility” or “at will”. In this context, it refers to keeping your mind and body free and ready for anything that might happen in times of need (also see the second half of the first golden principle).

3.) Take responsibility for your own body and actions.

This interpretation is based a sense of autonomy and self-responsibility in one’s training, including inside the dojo. It is grounded in the Japanese word 自発的 (jihatsuteki), meaning “voluntary” or “of one’s own accord”, and refers to the idea of not waiting to be taught by your sensei or senpai, but rather taking the initiative to work on your own development.

I have wanted to write a blog on this topic for some time now, but have finally managed to do so as I think the meaning of 心身自在 (shinshinjizai) truly reflects the main focus of the recent Jundokan seminar commemorating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Jundokan*, which was held in Okinawa from November 13~17th, 2024.

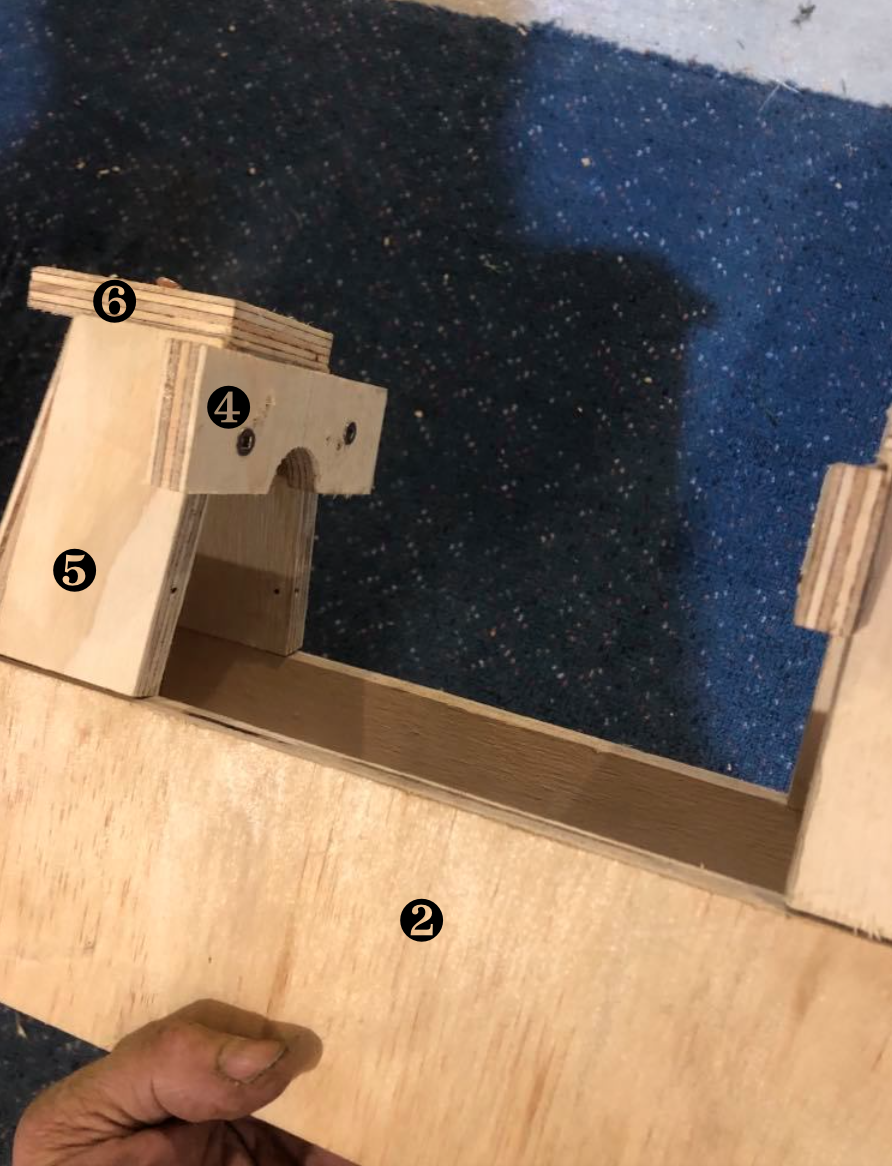

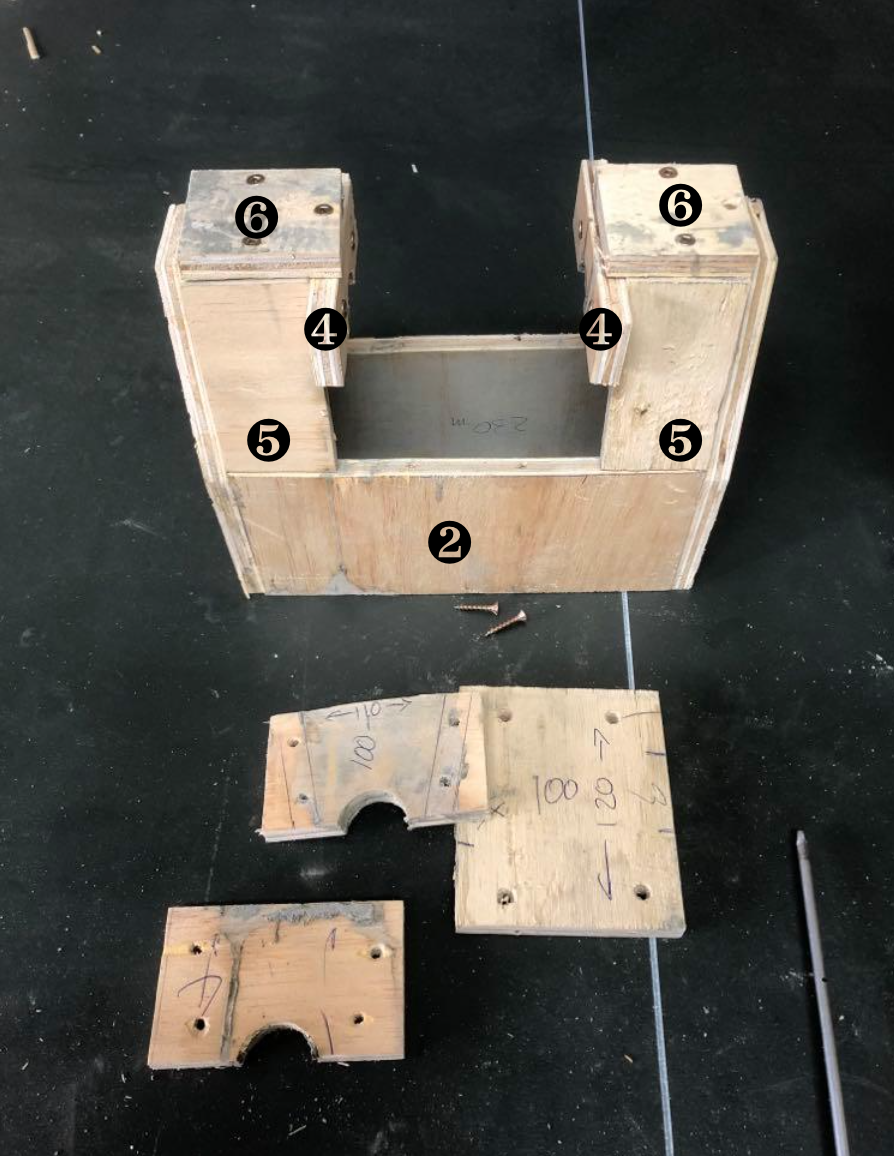

During this seminar, a lot of the instruction, particularly surrounding kata, was on learning and understanding the basic checkpoints for stances and hand positions. The idea behind which was, if you can understand how to check your own kata, you don’t need to wait for instruction from others, thus embodying the idea of taking control of your own actions and training.

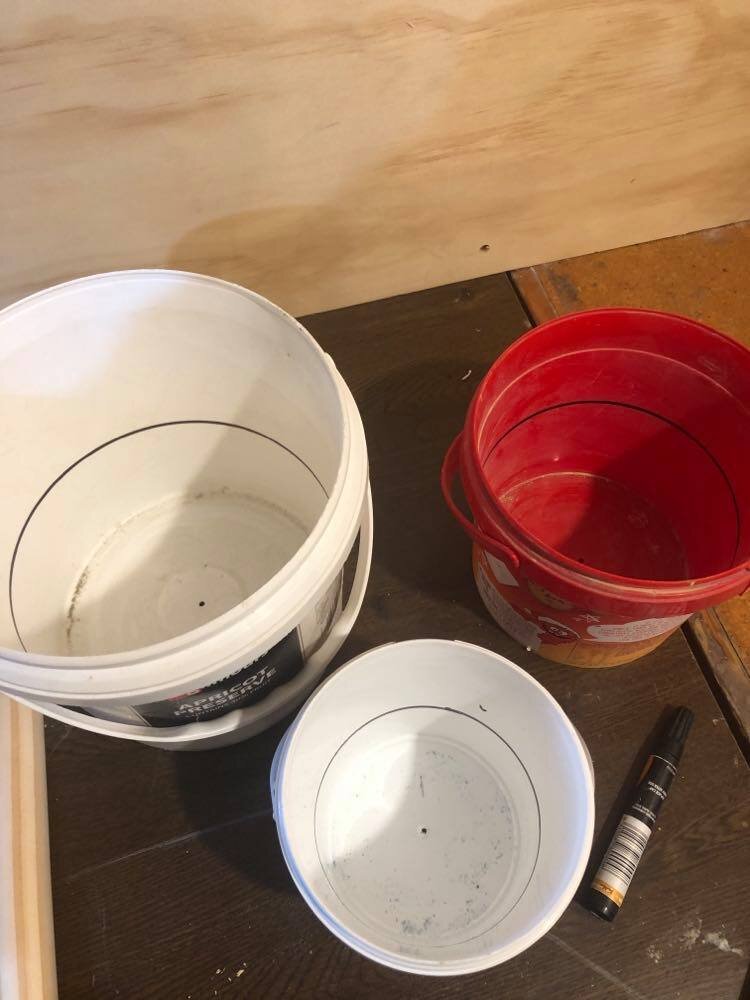

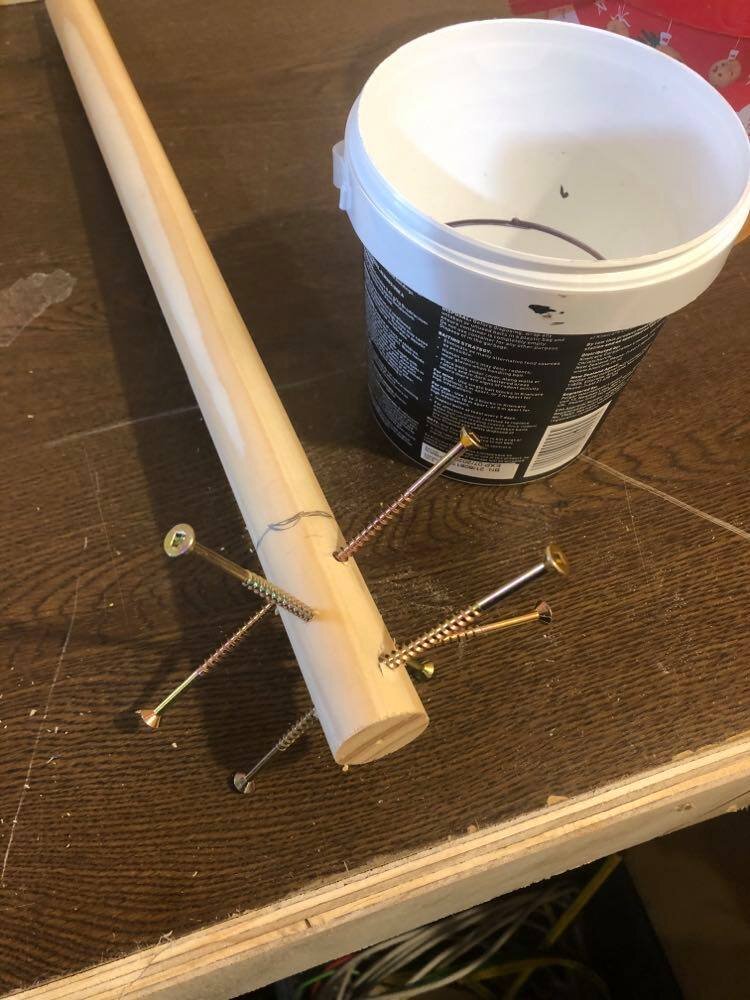

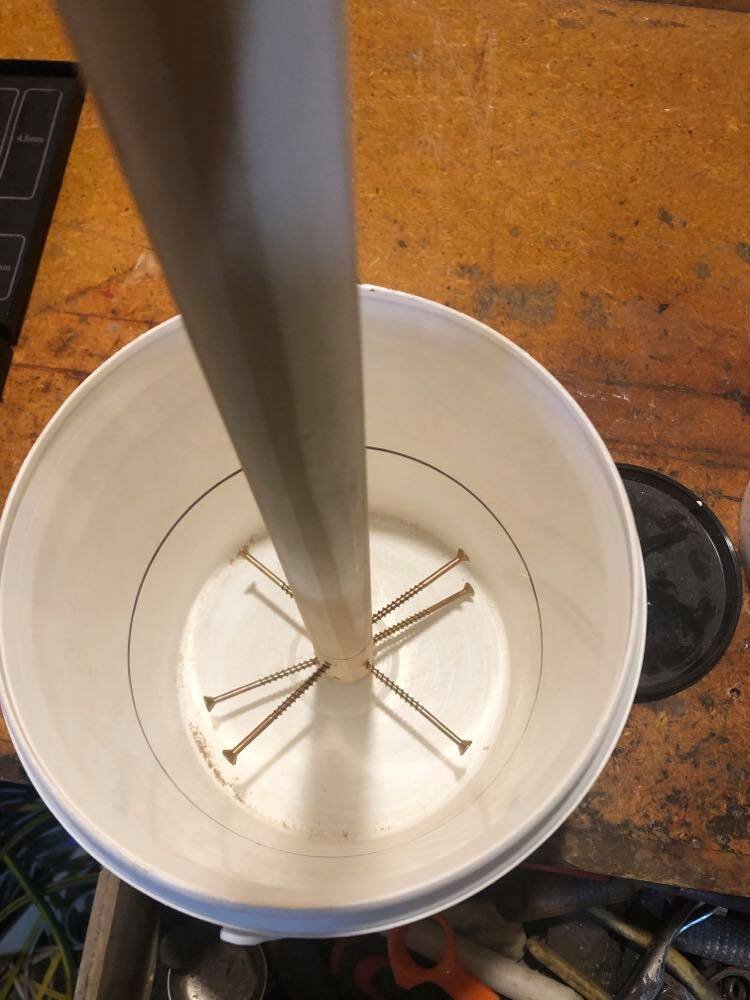

The photos below, taken at the seminar, show Gima-sensei and Kinjo-sensei explaining some of the basic checkpoints from the kata.

In conclusion, both 究道無限 (kyūdōmugen) and 心身自在 (shinshinjizai) are more than just philosophical ideals; they’re a call to action for karate practitioners to embody continuous study, independence, resilience, and accountability in both their training and daily lives. By not being swayed by others, maintaining control over mind and body, and taking responsibility for personal growth, we not only deepen our understanding of karate, but also cultivate a way of life that reflects its true spirit.

Blake Turnbull © 2024

* The Nov. 2024 seminar also commemorated the 70th Memorial of Miyagi Chojun-sensei, and the 25th Memorial of Miyazato Eiichi-sensei.